Etiological structure of acute intestinal infections based on the results of exterritorial monitoring

- Authors: Makarova M.A.1,2, Balde R.3, Kaftyreva L.A.1,2, Matveeva Z.N.4, Zhamborova S.K.1

-

Affiliations:

- St. Pasteur Institute

- I.I. Mechnikov North-Western State Medical University

- Research Institute of Applied Biology of Guinea

- St. Pasteur Institute, St. Petersburg

- Issue: Vol 102, No 4 (2025)

- Pages: 436-444

- Section: ORIGINAL RESEARCHES

- URL: https://microbiol.crie.ru/jour/article/view/18925

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.36233/0372-9311-722

- EDN: https://elibrary.ru/XSKWOC

- ID: 18925

Cite item

Abstract

Introduction. Acute intestinal infections cause high morbidity and mortality, especially in Africa and Southeast Asia, where millions of children under the age of five die every year. The Republic of Guinea urgently requires large-scale research aimed at studying the causes of diarrheal diseases, necessary for the development of effective preventive measures to ensure the preservation of the health of its population.

Aim. To conduct a analysis of the etiological structure of acute intestinal infections in the Republic of Guinea.

Materials and methods. Stool samples (n = 724) from residents of the Republic of Guinea with diarrheal syndrome were studied by real-time PCR with two reagent kits: 1) AmpliSens OKI screen-FL for the detection of DNA (RNA) of microorganisms Shigella spp./EIEC, Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., Adenovirus, Rotavirus, Norovirus and Astrovirus; 2) AmpliSens Escherichiosis-FL for the detection of DNA of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli (DEC) of five pathogroups: EPEC, EHEC, ETEC, EIEC, EAgEC.

Results. In the period 2019-2022, 66.2% of the examined children and adults revealed the presence of genetic markers of acute intestinal infections, mainly of bacterial etiology (74.1%), among which diarrheagenic E. coli dominated (62.4%). Genetic markers of viral pathogens were detected significantly less frequently by 25.9%, p < 0.05. Young children are most vulnerable to infection caused by E. coli. Bacterial pathogens dominate both in cases of monoinfections and in cases of mixed infection with two or more types of pathogens.

Conclusion. A study has shown that DEC is the main cause of intestinal infections in Guinea. The data obtained will become the basis for the development of an effective program for the prevention and treatment of acute intestinal infections in the republic.

Full Text

Introduction

Acute intestinal infections are a global health problem, leading to high morbidity and mortality rates in many countries [1]. Approximately 1.6 million people die from diarrhea worldwide each year, with the vast majority of cases occurring in developing countries [2]. Diarrheal diseases are the cause of 15% of deaths in young children, with approximately 80% occurring in the regions of Africa and Southeast Asia [3, 4]. Despite a significant global reduction in diarrhea mortality over the past quarter-century, most African countries continue to face high prevalence rates of severe acute intestinal infections [5]. Experts estimate that by 2030, 4.4 million children under the age of 5 will die annually from infectious diseases, with 60% of cases occurring in African countries [6, 7].

For the African continent, diarrheal diseases remain a pressing threat, particularly acute in conditions of deep poverty [8–10]. Within the UN Millenium Declaration adopted in 2000, important goals were set aimed at combating poverty and malnutrition, ensuring universal access to clean drinking water, and significantly reducing child mortality1. However, current realities show that many African countries will not be able to achieve these targets on time, considering that only a third of the population has regular access to clean water [11–13]. This fact creates additional risks of diarrheal diseases spreading among a significant portion of the region's population2.

According to data from the international Global Enterics Multi-Center Study (GEMES) project, diarrheagenic Escherichia coli (DEC) and Cryptosporidium are recognized as the most dangerous pathogens causing deaths from diarrhea in children under 5 years old in several African countries — Kenya, Mali, Mozambique and Gambia. Research conducted in 18 African countries on the burden of diarrheal diseases of Escherichia coli etiology showed that enteroaggregative E. coli (EAgEC) are a more common DEC pathogenic group (69% of cases) than enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) and enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC), with prevalence ranging from 6.6% to 18.6% [2].

Unlike developed regions such as the United States and Europe, which have well-organized systems for monitoring intestinal infections, including DEC3, most countries on the African continent face significant challenges in developing effective healthcare infrastructure and comprehensive control of acute intestinal infections.

The etiology of acute intestinal infections is diverse, which leads to differences in the epidemic process in countries with varying levels of economic development. This is the reason why identifying the key pathogens causing gastrointestinal infectious diseases is crucial for organizing microbiological monitoring within the epidemiological surveillance system and preventing infectious threats in African countries. Nowadays, Guinea has a particular necessity for large-scale research aimed at studying the etiology of acute diarrhea to develop a regional strategy for preventing diarrheal diseases, which is essential for preserving the health of the Republic population.

The aim of the study is to conduct a systematic analysis of the etiological structure of acute intestinal infections in the Republic of Guinea.

Materials and methods

The study included patients who sought medical attention at healthcare facilities with symptoms of acute intestinal infection (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, symptoms of intoxication). The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pasteur St. Petersburg Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology (protocol No. 27 dated 02.07.2019).

Stool samples from 724 patients, including 73 children aged 1–5 years (10.1%), 130 aged 6–17 years (18.0%) and 521 adults aged 18–76 years (72.0%), were examined using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with hybridization-fluorescence detection with two reagent kits:

- AmpliSens OKI screen-FL for the detection and differentiation of DNA (RNA) of microorganisms of the Shigella/EIEC, Salmonella spp., thermophilic Campylobacter spp., Adenovirus (group F), Rotavirus (group A), Norovirus (genotype 2) and Astrovirus;

- AmpliSens Escherichiosis-FL for the detection of diarrheagenic coli (DEC) of 5 pathogenic groups: EPEC, EHEC, ETEC, EIEC, EAgEC (Russian Research Institute of Epidemiology of Rospotrebnadzor, Russia).

Total DNA/RNA was extracted using the RIBO-prep reagent kit (Russian Research Institute of Epidemiology of Rospotrebnadzor, Russia). PCR was performed using thermocycler with a real-time fluorescent signal detection system (real-time PCR) CXT-1000 (Bio-Rad). All nucleic acid extraction and real-time PCR procedures used in this study were performed using appropriate positive, negative and internal control samples included in the diagnostic kits. The use of controls at all stages allowed for confirmation of the correctness and accuracy of the results obtained, eliminating the possibility of false positive or false negative conclusions.

Targeted screening for Shigella spp. and EIEC strains was performed on stool samples that yielded a fluorescent signal for the presence of Shigella spp./EIEC (AmpliSens OKI screen-FL) and EIEC (AmpliSens Escherichia coli-FL). E. coli were isolated using the cultural method with selective media Endo and Hektoen agar (State Research Center for Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology).

Fisher's exact test was used to assess the statistical significance of differences in mean values. The significance of the differences between the studied indicators was determined using the Mann–Whitney test. Significant differences were considered at a 95% confidence interval (p ≤ 0.05).

The studies were conducted in the laboratory of the Russian-Guinean Research Center for Epidemiology and Prevention of Infectious Diseases as part of the research project "Study of the Etiological Structure and Molecular-Genetic Characterization of Diarrheal Pathogens in the Republic of Guinea”.

Results

According to the combined data, between 2019 and 2022, genetic markers of viral and bacterial pathogens of acute intestinal infections were detected in stool samples from 479 (66.2%) examined individuals: in 238 (49.7%; 95% CI 45.2–54.2%) men and 241 (50.3%; 95% CI 45.9–54.8%) women (p > 0.05). Determinants of the pathogens of interest were more frequently detected in the age group of patients 18 years and older — 331 (69.1%; 95% CI 64.8–73.1%; p ≤ 0.05). No significant differences were found in the detection rate of DNA/RNA of pathogens causing acute intestinal infections in samples from young children (n = 59; 12.3%, 95% CI 9.7–15.6%) and school-aged children (n = 89; 18.6%; 95% CI 15.5–22.3%) (Mann–Whitney test). No statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) were found in the detection frequency of genetic markers of acute intestinal infections of established etiology based on sex and age, both in the combined data and separately by year (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Detection rates of genetic markers of acute intestinal infections in residents of the Republic of Guinea in 2019–2022.

Genetic markers of the studied pathogens were not detected in samples from 245 patients with diarrhea syndrome, thus infections of unknown etiology accounted for 33.8% on average over the multi-year period.

The results of the molecular study, by year and in total, are presented in Table 1 and Table 2. Throughout all years of observation, bacterial pathogens significantly predominated over viral ones in the etiological structure of acute intestinal infections (р ≤ 0,05).

Table 1. Detection rates of genetic markers of enteropathogens in residents of the Republic of Guinea in 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022

Year | Pathogen | Total | Monoinfection | Combined infections | |||

n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

2019 | Bacterial | ||||||

Campylobacter spp. | 6 | 7.3 | 5 | 6.1 | 1 | 1.2 | |

Salmonella spp. | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

DEC | 38 | 46.3 | 36 | 43.9 | 2 | 2.4 | |

Total bacterial | 44 | 53.7 | 41 | 50.0 | 3 | 3.7 | |

Viral | |||||||

Adenovirus | 30 | 36.6 | 8 | 9.8 | 22 | 26.8 | |

Astrovirus | 2 | 2.4 | 1 | 1.2 | 1 | 1.2 | |

Norovirus | 3 | 3.7 | 2 | 2.4 | 1 | 1.2 | |

Rotavirus | 3 | 3.7 | 2 | 2.4 | 1 | 1.2 | |

Total viral | 38 | 46.3 | 13 | 15.9 | 25 | 30.5 | |

Total enteropathogens | 82 | 100.0 | 54 | 65.9 | 28 | 34.1 | |

2020 | Bacterial | ||||||

Campylobacter spp. | 6 | 5.1 | 1 | 0.8 | 5 | 4.2 | |

Salmonella spp. | 6 | 5.1 | 1 | 0.8 | 5 | 4.2 | |

DEC | 72 | 61.0 | 51 | 43.2 | 21 | 17.8 | |

Total bacterial | 84 | 71.2 | 53 | 44.9 | 31 | 26.3 | |

Viral | |||||||

Adenovirus | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

Astrovirus | 2 | 1.7 | 2 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

Norovirus | 9 | 7.6 | 4 | 3.4 | 5 | 4.2 | |

Rotavirus | 23 | 19.5 | 10 | 8.5 | 13 | 11.0 | |

Total viral | 34 | 28.8 | 16 | 13.6 | 18 | 15.3 | |

Total enteropathogens | 118 | 100 | 69 | 58.5 | 49 | 41.5 | |

2021 | Bacterial | ||||||

Campylobacter spp. | 32 | 14.7 | 14 | 6.5 | 18 | 8.3 | |

Salmonella spp. | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | |

DEC | 142 | 65.4 | 98 | 45.2 | 44 | 20.3 | |

Total bacterial | 175 | 80.6 | 113 | 52.1 | 62 | 28.6 | |

Viral | |||||||

Adenovirus | 19 | 8.8 | 7 | 3.2 | 12 | 5.5 | |

Astrovirus | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.9 | |

Norovirus | 19 | 8.8 | 6 | 2.8 | 13 | 6.0 | |

Rotavirus | 2 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | |

Total viral | 42 | 19.4 | 14 | 6.5 | 28 | 12.9 | |

Total enteropathogens | 217 | 100 | 127 | 58.5 | 90 | 41.5 | |

2022 | Bacterial | ||||||

Campylobacter spp. | 3 | 4.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 4.8 | |

Salmonella spp. | 2 | 3.2 | 1 | 1.6 | 1 | 1.6 | |

DEC | 47 | 75.8 | 35 | 56.5 | 12 | 19.4 | |

Total bacterial | 52 | 83.9 | 36 | 58.1 | 16 | 30.8 | |

Viral | |||||||

Adenovirus | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

Astrovirus | 4 | 6.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 6.5 | |

Norovirus | 1 | 1.6 | 1 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

Rotavirus | 5 | 8.1 | 3 | 4.8 | 2 | 3.2 | |

Total viral | 10 | 16.1 | 4 | 6.5 | 6 | 9.7 | |

Total enteropathogens | 62 | 100.0 | 40 | 64.5 | 22 | 35.5 | |

Table 2. Detection rates of genetic markers of enteropathogens in residents of the Republic of Guinea with diarrheal syndrome in 2019–2022

Pathogen | Total | Monoinfection | Combined infections | |||

n | % | n | % | n | % | |

Bacterial | ||||||

Campylobacter spp. | 47 | 9.8 | 20 | 4.2 | 27 | 5.6 |

Salmonella spp. | 9 | 1.9 | 3 | 0.6 | 6 | 1.3 |

DEC: | 299 | 62.4 | 220 | 45.9 | 79 | 16.5 |

EAgEC | 140 | 46.8 | 83 | 27.8 | 57 | 19.1 |

EPEC | 60 | 20.1 | 35 | 19.7 | 6 | 0.3 |

ETEC | 39 | 13.0 | 32 | 10.7 | 7 | 2.3 |

EIEC | 41 | 13.7 | 59 | 11.7 | 1 | 2.0 |

STEC | 19 | 6.4 | 11 | 3.7 | 8 | 2.7 |

Total bacterial | 355 | 74.1 | 243 | 50.7 | 112 | 23.4 |

Viral | ||||||

Adenovirus | 49 | 10.2 | 15 | 3.1 | 34 | 7.1 |

Astrovirus | 10 | 2.1 | 3 | 0.6 | 7 | 1.5 |

Norovirus | 32 | 6.7 | 13 | 2.7 | 19 | 4.0 |

Rotavirus | 33 | 6.9 | 16 | 3.3 | 17 | 3.5 |

Total viral | 124 | 25.9 | 47 | 9.8 | 77 | 16.1 |

Total enteropathogens | 479 | 100.0 | 290 | 60.5 | 189 | 39.5 |

DNA of bacterial pathogens was detected in 355 (74.1%; 95% CI 70.1–77.8%) samples, of which Campylobacter spp. accounted for 9.8% (95% CI 7.5–12.9%), Salmonella spp. for 1.9% (95% CI 1.0–3.5%), and DEC for 62.4% (95% CI 57.9–66.7%). Viral pathogens accounted for 25.1% (95% CI 22.2–30.0%), of which Adenovirus accounted for 10.2% (95% CI 7.8–13.3%), Rotavirus for 6.9% (95% CI 4.9–9.5%), Norovirus for 6.7% (95% CI 4.8–9.3%), and Astrovirus for 2.1% (95% CI 1.1–3.8%).

The leading pathogens throughout all years of surveillance were DEC. In the age structure, they were significantly more common in young children aged 0–5 years (91.7%; 95% CI 82.7–96.9%; p ≤ 0.05) compared to the group of school-aged children aged 6–17 years (53.9%; 95% CI 44.9–62.8%) and adults (45.6%; 95% CI 41.3–50.0%). According to the combined data, a significant prevalence of the EAgEC pathogenic group was identified both in the structure of escherichioses (46.8%; 95% CI 41.2–52.5%) and in the overall structure of acute intestinal infections (29.3%; 95% CI 25.3–33.5%; p ≤ 0.05). In the multi-year structure of Escherichia coli infections, other DEC pathogenic groups: EPEC, ETEC and EIEC accounted for 20.1%, 13.0% and 13.7%, respectively. Findings of genetic determinants of STEC were less frequent compared to other DEC pathogenic groups, with their share being 6.4% based on cumulative data.

Genetic markers of bacterial pathogens were detected significantly more often compared to viral pathogens (p ≤ 0.05) in all years of monitoring, as well as cumulatively during the study period.

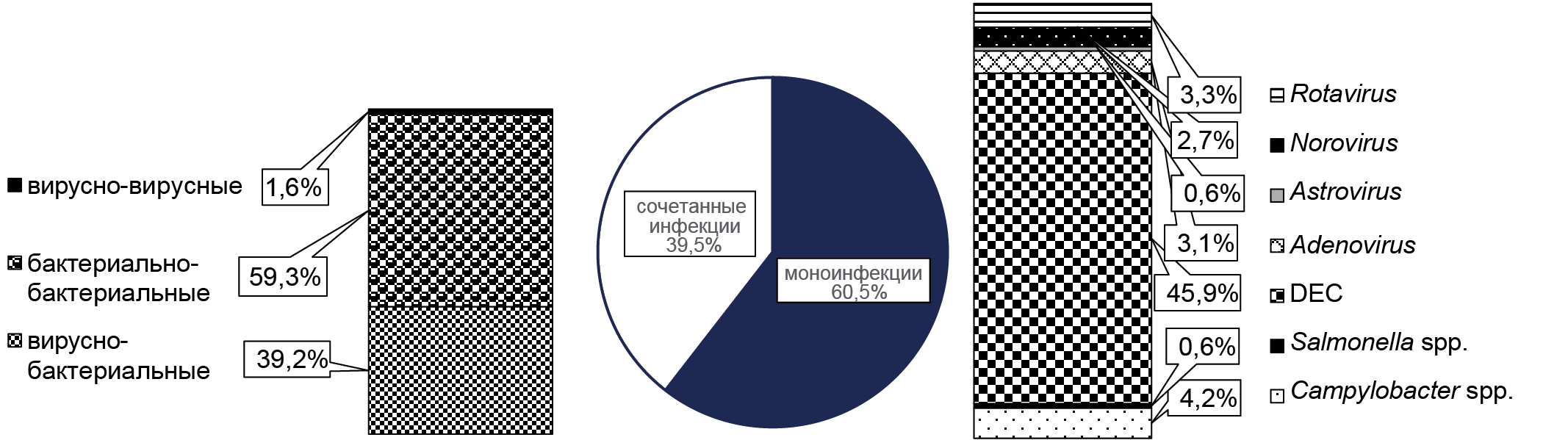

Monoinfections caused by a single type of enteric pathogen prevailed over combined etiology enteric infections in all years of surveillance (Fig. 2). In 290 (60.5%; 95% CI 56.1–64.8%) positive samples, genetic markers of a single pathogen were detected, with DEC being significantly more frequent at 45.9% (95% CI 43.2–56.5%) compared to other bacterial pathogens (Campylobacter spp. — 4.2%; 95% CI 0–6.5%; Salmonella spp. — 0.6%; 95% CI 0–1.6%) and viral nature 47 (9.8%) (Adenovirus — 3.1%; 95% CI 0–9.8%; Astrovirus — 0.6%; 95% CI 0–1.7%; Norovirus — 2.7%; 95% CI 1.6–3.4%; Rotavirus — 3.3%; 95% CI 0.5–8.5%). Analysis of molecular studies revealed the presence of two or more genetic markers of the investigated acute intestinal infections in 189 (39.5%; 95% CI 35.2–43.9%) samples, of which viral-bacterial were found in 74 (39.2%), bacterial-bacterial in 112 (59.3%) and viral-viral in 3 (1.6%).

Fig. 2. Characteristics of acute intestinal infections in the Republic of Guinea in 2019–2020.

Discussion

Diarrheal diseases in children and adults are a pressing issue in the Republic of Guinea. It was established that the main pathogens of diarrheal diseases are representatives of anthroponotic infections — 363 (75.8%), of which viral (Adenovirus, Astrovirus, Norovirus, Rotavirus) accounts for 25.9% (95% CI 22.2–30.0%), and bacterial (EAgEC, EPEC, ETEC, EIEC) accounts for 58.5% (95% CI 54.0–62.8%). The results obtained confirm that the pathogens of anthroponotic infections are more prevalent in developing countries compared to foodborne pathogens such as Salmonella, Campylobacter and STEC in industrialized countries [14–16]. Genetic markers for Salmonella were identified in 9 (1.9%) cases, for Campylobacter in 47 (9.8%), and for STEC in 19 (6.4%). This allows for the assumption that meat and dairy products are insufficient in the diet of the people of Guinea (children and adults), but this issue requires further study.

In the study conducted, genetic markers of Rotavirus were identified in only 33 (6.9%) patients, despite this pathogen being the most common cause of severe gastroenteritis in children in many economically developed countries, accounting for 30–72% of hospitalized patients and 4–24% of patients with mild acute gastroenteritis not requiring hospitalization. The absence of this pathogen in the etiological structure of acute intestinal infections may be related to rotavirus vaccination [17].

Monitoring revealed that DEC were the main cause of acute intestinal infections (62.4%). The use of molecular methods allowed for the assessment of the structure of E. coli infections and the identification of all known DEC pathogenic groups within the territory of the Republic of Guinea. According to the combined data, strains of EAgEC predominated in the structure of escherichioses in all years of surveillance, accounting for 46.8%. Studies conducted in Latin America, Asia, Africa and Eastern European countries have shown that EAgEC are more frequent causes of diarrhea in children than other bacterial pathogens [18–20]. Data obtained in the USA, Europe and Israel also indicate that EAgEC often cause diarrheal diseases in children [21]. In the United States, the incidence of E. coli infections caused by EAgEC is higher in young children than that of campylobacteriosis and salmonellosis [22].

Epidemiological studies in West African countries (Mali, Gambia, Burkina Faso) have detected the presence of DEC in well drinking water and in packaged sachets (water sachets, packaged water), indicating the possibility of human infection with these microorganisms. The results obtained are important for understanding the epidemiology of escherichiosis and are of interest for studying similar problems in neighboring African countries, including the Republic of Guinea [19, 23].

Overall, 290 (60.5%) residents of the Republic of Guinea were found to have genetic markers of a single enteric pathogen, and monoinfection was identified based on laboratory results. In 189 (39.5%) of the examined individuals, an association of enteropathogens was established (combined acute intestinal infections). A high prevalence of combined infections (25–53%) has been described in developing countries [24, 25]. DEC predominated in all combined infections, which is consistent with literature data [19, 20].

The use of a multiplex format in laboratory diagnostics of acute intestinal infections is currently the only highly sensitive method that allows for the establishment of the etiology of acute intestinal infections not only in the acute phase of the disease but also in asymptomatic bacterial carriage. A large-scale study conducted in Ethiopia using modern laboratory diagnostic methods showed that in 56.3% of cases, diarrheal syndrome is caused by bacterial, viral and/or parasitic pathogens, and importantly, it allowed for the identification of mixed infections in 35% of cases [26–28].

The study confirmed the relevance of diarrheagenic E. coli for the population of the Republic of Guinea, as well as for other African countries [2, 3, 7, 9, 19]. Laboratory diagnosis of these pathogens is only possible using molecular methods [29].

Conclusion

The etiology of acute intestinal infections in the Republic of Guinea includes bacterial and viral pathogens. The study showed that DEC were the cause of diarrheal illness in almost every other patient, which confirmed their relevance in the structure of acute intestinal infections. To reduce the burden of diarrheal diseases in Guinea, targeted epidemiological and microbiological studies are needed to identify DEC, investigate environmental contamination, including water and food, and determine risk factors. Given that diarrhea is a polyetiological disease, it is necessary to implement a comprehensive, rapid, reliable and accessible method for identifying a wide range of pathogens.

The first detailed analysis of the etiological structure of acute intestinal infections in the Republic of Guinea provides a basis for the development of evidence-based policies for the prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal infectious diseases. Such research will allow us to respond to new threats, reduce morbidity and use healthcare resources more effectively. Successful prevention of diarrheal infections requires measures such as analyzing transmission pathways, ensuring quality drinking water, increasing the population's sanitation literacy and establishing an epidemiological monitoring system. The incorporation of PCR diagnostics into routine medical practice in the Republic of Guinea will be a significant contribution to improving public health and reducing the incidence of gastrointestinal infectious diseases.

1 United Nations Millennium Declaration. URL: https://www.un.org/ru/documents/decl_conv/declarations/summitdecl.shtml

2 WHO. Diarrhoeal disease; 2024. URL: https://who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease

3 National Surveillance of Bacterial Foodborne Illness (Enteric Diseases). URL: https://www.cdc.gov/nationalsurveillance/index.html; Surveillance and disease data for Escherichia coli. URL: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/escherichia-coli-ecoli/surveillance-and-disease-data

About the authors

Maria A. Makarova

St. Pasteur Institute; I.I. Mechnikov North-Western State Medical University

Author for correspondence.

Email: makmaria@mail.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0003-3600-2377

Dr. Sci. (Med.), Assistant Professor, senior researcher, Head, Laboratory of enteric infection, St. Pasteur Institute, Professor, Department of medical microbiology, I.I. Mechnikov North-Western State Medical University

Russian Federation, St. Petersburg; St. PetersburgRamatoulay Balde

Research Institute of Applied Biology of Guinea

Email: balderamatoulaye025@gmail.com

ORCID iD: 0009-0005-7945-3807

Researcher, Department of bacteriology

Guinea, KindiaLidiya A. Kaftyreva

St. Pasteur Institute; I.I. Mechnikov North-Western State Medical University

Email: kaflidia@mail.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0003-0989-1404

Dr. Sci. (Med.), Head, Microbiological department, St. Pasteur Institute, St. Petersburg, Department of medical microbiology, I.I. Mechnikov North-Western State Medical University

Russian Federation, St. Petersburg; St. PetersburgZoya N. Matveeva

St. Pasteur Institute, St. Petersburg

Email: z_matveeva56@mail.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-7173-2255

Cand. Sci. (Med.), leading researcher, Laboratory of enteric infection

Russian Federation, St. PetersburgSamida Kh. Zhamborova

St. Pasteur Institute

Email: zhamborova.m@mail.ru

ORCID iD: 0009-0009-9620-9784

Researcher, Laboratory of enteric infection

Russian Federation, St. PetersburgReferences

- Hartman R.M., Cohen A.L., Antoni S., et al. Risk factors for mortality among children younger than age 5 years with severe diarrhea in low- and middle-income countries: findings from the World Health Organization-coordinated Global Rotavirus and Pediatric Diarrhea Surveillance Networks. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023;76(3):e1047–53. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciac561

- Kalule J.B., Bester L.A., Banda D.L., et al. Molecular epidemiology and AMR perspective of diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health. 2024;14(4):1381–96. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44197-024-00301-w

- Manhique-Coutinho L., Chiani P., Michelacci V., et al. Molecular characterization of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli isolates from children with diarrhea: a cross-sectional study in four provinces of Mozambique: diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in Mozambique. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022;121:190–4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2022.04.054

- Vorlasane L., Luu M.N., Tiwari R., et al. The clinical characteristics, etiologic pathogens and the risk factors associated with dehydration status among under-five children hospitalized with acute diarrhea in Savannakhet Province, Lao PDR. PLoS One. 2023;18(3):e0281650. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281650

- Khairy R.M.M., Fathy Z.A., Mahrous D.M., et al. Prevalence, phylogeny, and antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli pathotypes isolated from children less than 5 years old with community acquired- diarrhea in Upper Egypt. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020;20(1):908. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05664-6

- Tang X., Oyetoran A., Jones T., Bray C. Aeromonas caviae-associated severe bloody diarrhea. Case Rep. Gastrointest. Med. 2023;2023:4966879. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/4966879

- Wolde D., Tilahun G.A., Kotiso K.S., et al. The Burden of diarrheal diseases and its associated factors among under-five children in Welkite Town: a community based cross-sectional study. Int. J. Public Health. 2022;67:1604960. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2022.1604960

- Kemajou D.N. Climate variability, water supply, sanitation and diarrhea among children under five in Sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel analysis. J. Water Health. 2022;20(4):589–600. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2022.199

- Grenov B., Lanyero B., Nabukeera-Barungi N., et al. Diarrhea, dehydration, and the associated mortality in children with complicated severe acute malnutrition: a prospective cohort study in Uganda. J. Pediatr. 2019;210:26–33.e3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.03.014

- Adane M., Mengistie B., Medhin G., et al. Piped water supply interruptions and acute diarrhea among under-five children in Addis Ababa slums, Ethiopia: a matched case-control study. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181516. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181516

- Gavhi F., Kuonza L., Musekiwa A., Motaze N.V. Factors associated with mortality in children under five years old hospitalized for severe acute malnutrition in Limpopo province, South Africa, 2014–2018: a cross-sectional analytic study. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0232838. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232838

- Ellis S.J., Crossman L.C., McGrath C.J., et al. Identification and characterisation of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli subtypes associated with human disease. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):7475. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64424-3

- Getahun W., Adane M. Prevalence of acute diarrhea and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) associated factors among children under five in Woldia Town, Amhara Region, northeastern Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):227. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-02668-2

- Hlashwayo D.F., Sigaúque B., Noormahomed E.V., et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis reveal that Campylobacter spp. and antibiotic resistance are widespread in humans in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0245951. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245951

- Kotloff K.L. Bacterial diarrhoea. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2022;34(2):147–55. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000001107

- GBD 2019 Under-5 Mortality Collaborators. Global, regional, and national progress towards Sustainable Development Goal 3.2 for neonatal and child health: all-cause and cause-specific mortality findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2021;398(10303):870–905. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01207-1

- Boisen N., Østerlund M.T., Joensen K.G., et al. Redefining enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC): genomic characterization of epidemiological EAEC strains. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020;14(9):e0008613. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008613

- Ochieng J.B., Powell H., Sugerman C.E., et al. Epidemiology of enteroaggregative, enteropathogenic, and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli among children aged <5 years in 3 countries in Africa, 2015–2018: Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa (VIDA) study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023;76(76 Suppl. 1): S77–86. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad035

- Modgil V., Mahindroo J., Narayan C., et al. Comparative analysis of virulence determinants, phylogroups, and antibiotic susceptibility patterns of typical versus atypical enteroaggregative E. coli in India. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020;14(11):e0008769. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008769

- Van Nederveen V., Melton-Celsa A.R. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC). EcoSal Plus. 2025;eesp00112024. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1128/ecosalplus.esp-0011-2024

- Wikswo M.E., Roberts V., Marsh Z., et al. Enteric illness outbreaks reported through the national outbreak reporting system — United States, 2009–2019. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022;74(11):1906–13. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab771

- Bonkoungou I.J.O., Somda N.S., Traoré O., et al. Detection of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in human diarrheic stool and drinking water samples in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Afr. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;15(1):53–8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21010/ajid.v15i1.7

- Poeta M., Del Bene M., Lo Vecchio A., Guarino A. Acute infectious diarrhea. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2024;1449:143–56. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-58572-2_9

- Meisenheimer E.S., Epstein C.D.O., Thiel D. Acute diarrhea in adults. Am. Fam. Physician. 2022;106(1):72–80.

- Lääveri T., Antikainen J., Mero S., et al. Bacterial, viral and parasitic pathogens analysed by qPCR: findings from a prospective study of travellers' diarrhoea. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2021;40:101957. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101957

- Çimen B., Aktaş O. Distribution of bacterial, viral and parasitic gastroenteritis agents in children under 18 years of age in Erzurum, Turkey, 2010–2020. Germs. 2022;12(4):444–51. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18683/germs.2022.1350

- Bhat A., Rao S.S., Bhat S., et al. Molecular diagnosis of bacterial and viral diarrhoea using multiplex-PCR assays: an observational prospective study among paediatric patients from India. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2023;41:64–70. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmmb.2023.01.002

- Макарова М.А. Современное представление о диареегенных Escherichia coli — возбудителях острых кишечных инфекций. Журнал микробиологии, эпидемиологии и иммунобиологии. 2023;100(4):333–44. Makarova M.A. A modern view of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli – a causative agent of acute intestinal infections. Journal of Microbiology, Epidemiology and Immunobiology. 2023;100(4):333–44. DOI: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.36233/0372-9311-410 EDN: https://elibrary.ru/rnmhnb

Supplementary files